Blog

Beyond the Rainbow – IR Photography

Seeing the world in infrared opens up awhole new universe for the creative photographer. You might think that the picture of the palm tree was a night shot, but it was taken in bright sunlight.

Image 1 – at the Auckland Domain on a bright summer afternoon

Infrared (IR) photography has a strong appeal for fine art photography. It is also a great tool for the wedding and portrait photographer. Skin tones come out much softer and blemishes tend to disappear.

A few months ago I decided to take the plunge and get myself an IR camera. As I will explain later, there are two options: You can use your existing camera with an external IR filter on your lenses, or you get a dedicated IR camera. I went for the second option and I’ll explain some of the pros and cons.

IR and the Visible Spectrum

Image 2 – The Spectral Range – UV to IR

Let’s start with some theory. IR is what comes beyond the red end of the rainbow. Our eyes can’t see it. The visible light spectrum extends from around 380 to 700 nm (nanometres), a small window in the electromagnetic spectrum. Sun light extend well beyond both ends. At the shorter wavelengths we have the transition to ultraviolet radiation, which we block out with UV filters. At the other end, the spectrum leads into the photographically interesting near infrared region from 700 to around 1200 nm, just beyond visible red. Further down the line you’ll get the far IR, which is heat.

Normal film is not sensitive to IR and there is no need for an IR block filter. When working with infrared sensitive film, you use an ‘IR filter’ to block out the visible spectrum. IR photography is not simply an extension of the visible light region into the infrared. Visible light is deliberately eliminated, and IR filters have a certain cut-off between 650 and 1000 nm. The camera captures only the IR reflected off whatever is in front of your lens. The blue sky turns dark simply because it doesn’t reflect any IR.

What stands out in most IR photos is the bright foliage. It often looks like a winter landscape. This strong reflection from green vegetation is called the “Wood Effect” (after the IR photography pioneer Robert Wood, around 1910). There is a small contribution from chlorophyll fluorescence, but it is marginal and not the real cause of the bright vegetation.

Digital IR Photography

All image sensors are sensitive to infrared radiation. They were used in security cameras long before they got into our digital cameras. In fact, IR needs to be blocked out for normal photography. The early generations of digital cameras did a poor job with filtering out IR, but today’s cameras have more effective IR block filters sandwiched in front of the sensor. With the absolute certainty of losing your camera guarantee, the more courageous enthusiast can try and replace this piece of glass with a suitable IR filter (which blocks out visible light). It is not for the faint of heart and of course makes the camera useless for conventional photography.

If you want to explore the world in IR you have two options. You can use your existing camera and put an IR filter in front your lens. There are different types available that cut off visible light below around 660, 710, 850 or 1000 nm. These filters don’t come cheap, especially if you need a larger size for your wide-angle zoom. Cutting out the visible light is a fancy way of saying that these filters are black! Because of the built-in IR block filter, only a trickle of IR is going to get through to the sensor. A tripod is essential, and you need to compose your image, then put the filter on, refocus (because IR focuses differently to shorter wavelengths), and then work out the exposure. Count on exposure times going from several seconds into minutes.

The other option is to get a dedicated IR camera (assuming you didn’t go for the DIY job!).

Choosing Camera and Filter

There are a couple of companies that offer to convert your old camera into a dedicated IR shooter, or they start from a brand new one. I chose Kolari Vision (kolarivision.com) and can highly recommend them. Their advice was helpful, their service excellent and the prices are very reasonable. My first choice was my old point-and-shoot Canon S90 which was gathering dust because I had replaced it with a newer model.

Unfortunately, this was a camera which was not recommended for IR modification because it was prone to ‘hotspots’. You need to go on their website to learn more about which cameras and lenses are suitable and which ones are not. I then settled for a Canon G16. Point-and-shoot cameras are a great option for getting started on IR photography. They are small and light, they don’t give you any hassles with focussing and exposure – and they don’t cost a fortune. Again, on their website you’ll find lots of information about choosing the best camera for you. It seems that the latest mirrorless cameras are best suited for IR work.

Next you need to select an IR filter which will be fitted in front of the sensor. The 720 nm is the standard classic IR filter. If you want a bit more colour coming through, you can opt for 590 or 665 nm. Then there is the 850 nm deep IR filter for the hard-core IR addict, which is only suited for B&W work.

Shooting in IR and Post processing

If you went for a simple point-and-shoot camera you’re ready to shoot away. The camera will set the right focus and exposure for you. With DSLRs you need to watch out for focus correction and exposure compensation.

And don’t wait for the evening light – IR photography is best done in mid-day under full sunshine! White balance is a nuisance, and the expert will recommend setting the customs white balance by pointing the camera at a batch of grass.

As a Raw file junky I don’t bother much with white balance, but when you open your files, they all come out pink and very dull-looking (Image 3). When setting the white balance in Adobe Lightroom or Camera Raw you’ll hit a wall on the left at 2000K, and IR shots need a lot less than that. Don’t worry about the red cast – we’ll fix that later with a hue and saturation adjustment and a channel swap.

Image 3 – A typical IR Shot Straight from the Camera

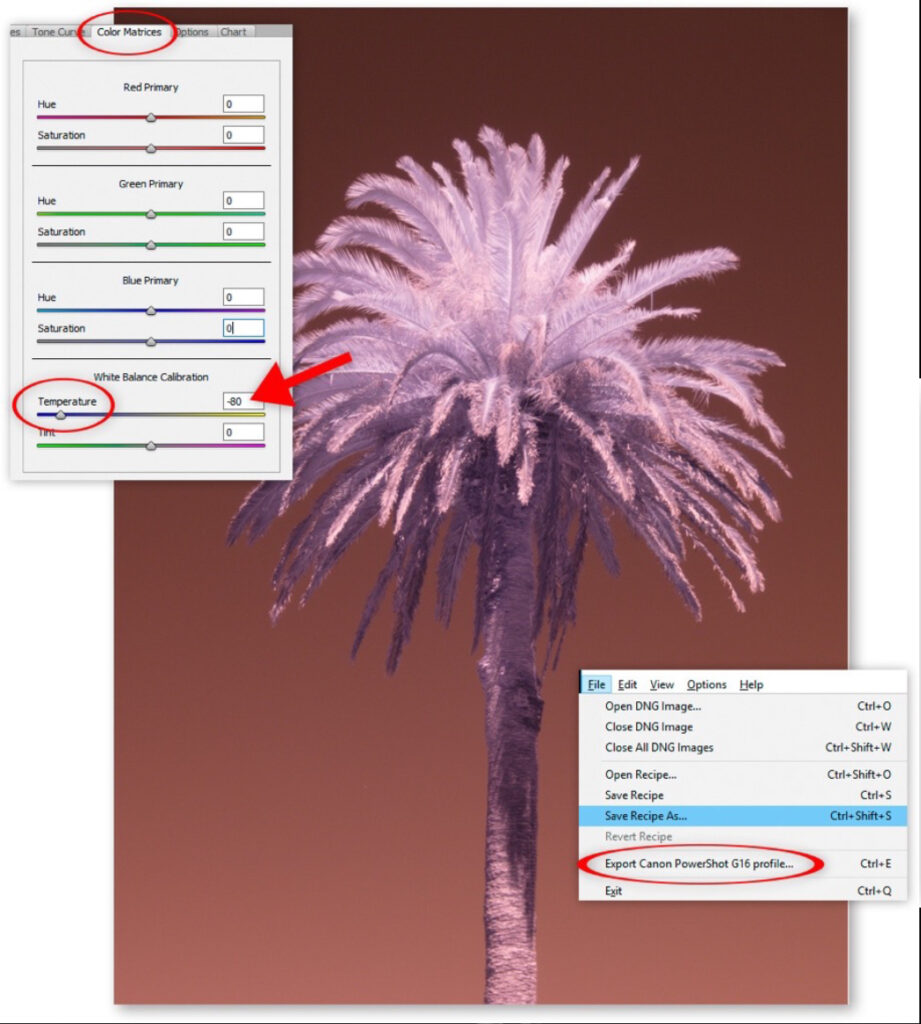

If you want to experiment more with the White Balance, you can download a tool called DNG Profile Editor from the Adobe website. This lets you recalibrate the Light Temperature in the White Balance setting to much less than 2000K. You need to save one of your files as a DNG file, then open it in the DNG Profile Editor. Go to the Colour Matrices tab and pull the Temperature slider down to around -80 (see Image 4). Finally, you export the profile after giving it a useful name, e.g. IR – Canon G16. Next time you open your Raw files you select the new profile, and you get the whole White Balance range to play with. But it is not essential to take this route.

Image 4 – Adobe’s DNG Profile Editor

Most IR photos are viewed as B&W images. If you opted for the classic 720 and 850 nm IR filters you’ll get B&W images anyway, straight out of the camera. All you need to do is increase the contrast.

For my camera conversion I opted for the 665 nm filter which lets a bit of visible light through, giving you some colour information. We’ll look at the colours just now, but if you want to turn your shots into classical B&W images, you need to convert them to B&W, and after some contrast tweaking, you’ll get something like Image 5, starting from Image 3. Don’t simply desaturate the image, but use the B&W Adjustment Layer tool, because there is plenty of colour information which lets you control the tonality of the various grey tones. Image 6 gives you the scene under familiar visible light. It was taken with my standard camera, just a few minutes later. The framing and the angle were not quite the same, but you get the idea.

Image 5 – Auckland War Memorial Museum in IR

Image 6 – Same shot as no.5, but in normal light

IR photography is full of surprises. A blue shirt might come out light or dark, depending on the material. A good example is my camera bag: it is black, but turned white in the IR shot. This makes sense, because the manufacturer used a material which reflects IR to keep the contents cool!

If you choose the 665 nm filter for your conversion (and even more so the 590 nm filter), you’ll have plenty of colour to play around with. Image 7 was taken from the museum, looking down towards the harbour. When opening the shot everything was pinkish as usual. To get a blue sky you need to swap the red and blue colour channels. This is best done with the Channel Mixer in Photoshop. Unfortunately, that’s something you can’t do in Lightroom. But you can use almost any image editor. The Kolari Vision website has a tutorial on how to use the free Gimp editor.

Image 7 – View from the Museum in IR

Image 8 – Swapping Channels using the Channel Mixer

This will give you a blue sky which you can selectively target with the Hue/Saturation tools. Leaves and grass take on a yellowish hue, which you can also perfect to your taste. I personally prefer the white tree effect to the cream-coloured hue (Image 9). It is easily achieved by desaturating the yellow in the leaves. Of course, you can apply any other Photoshop technique for maximum impact.

Image 9 – Blue Skies and White Trees

In the next issue we’ll look at more digital editing techniques around IR photography and simulating IR imaging.

© Digital Image NZ 2017